CHAPTER 2

Evolution of Lane County

After seeing the size-distance and size-type hypotheses fail nationally, I decided to try a detailed study of the origin of the boundaries of a single county, Lane County, Oregon, the location of the University. I was not intending to do anything formal (what Sociologists might call a "case study") — in fact, I had no specific expectations, nor could I hope that an explanation of Lane County's boundaries would apply anywhere else. But I was out of other ideas and hoped something would turn up. Needless to say, the University of Oregon library had an enormous collection of information on Oregon history for me to plow through.

Much of what I found — stories of the pioneering settlers, badly written verse ("Lo, yon verdant valley...", etc.) — was interesting but irrelevant. I found one article[1], however, which described the legislative acts creating most of the counties of Oregon. From this I learned that Lane was created on January 28, 1851 with a jurisdiction described as ... all that portion of Oregon Territory lying south of Linn County and south of so much of Benton County as is east of Umpqua CountyThis introduced two new puzzles. First, I knew nothing of the origin or extent of the Oregon Territory, so I had no way of interpreting "all that portion of Oregon Territory". And second, to understand Lane County's original boundary I would have to already know the boundaries of the other three counties mentioned. Here I review a little of what I learned. When the Oregon Territory was officially established by Congress on August 14, 1848, it was described as the territory of the United States lying "west of the summit of the Rocky Mountains, north of the forty-second degree of north latitude".[2] As can be seen from Fig. 2-2, this large territory included all or part of the current states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming.

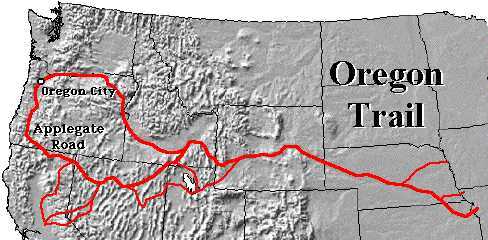

There was relevant history before that time, however,[3] beginning with its discovery. The coast is believed to have been sighted by Spanish and English sailors during the 1500s and 1600s. Captain James Cook, seeking the Northwest Passage, charted some of its coastline in 1778. In 1792 Captain Robert Gray discovered the river named after his ship, the Columbia, and claimed the area for the United States. It was explored by Lewis and Clark in 1805, and John Jacob Astor established his fur trading depot in 1811. The area was internationally recognized as being under joint British and American occupation from 1818, though there were many disputes between the British Hudson's Bay Company and the American settlers. By 1843 Americans began to arrive in increasing numbers with the "Great Emigration" along the 2,000-mile Oregon Trail. That same year a group of 120 Americans met at Oregon City to declare themselves the Provisional Government of the Oregon Territory. They established four counties (shown in Fig. 2-3) on July 5, 1843. In the Treaty of Oregon, 1846, Britain ceded any further claim to the territory below the 49th parallel. Actions taken by the Provisional Government were ratified by Congress when it created the territory in 1848.

The relevant boundaries of the three counties mentioned in the statute creating Lane County were given in statutes enacted earlier in the month. Linn and Benton Counties had been created earlier, in 1847. Umpqua probably was as well, though I cannot determine that with certainty (the county was dissolved sometime during 1851 or 1852). The southern boundary of Linn, January 4, 1851: ...commencing at west point, lying south of William Vaughn's claim, and running a westerly course to a point of the Wallamet [Willamette] River, at a distance of eight miles below Jacob Spoors', then at the place of beginning, due east to the Rocky Mountains.The southern boundary of Benton, January 15, 1851: ...commencing in the middle channel of the Wallamet River, at a point where a line, running west, will pass three miles south of the ford on Long Tom [River] near Roland Hinton's field, and running due west to the Pacific Ocean.The eastern boundary of Umpqua, January 24, 1851: [Beginning at a point where the south line of Benton County crosses the dividing ridge of the Calapooiah mountains], thence along the ridge of the said Calapooiah mountains, to the source of the main fork of the Calapooiah creek, thence down said creek to the mouth, thence due west to the Pacific Ocean.From these and earlier statutes[4], it would appear that Lane County fit into the already existing set as shown by Fig. 2-4, showing the original counties (here solely within what later became the state, i.e., territory south of the Columbia River) plus those created up to the time Lane was created.

Given these boundaries, and that of the Oregon Territory itself, the original jurisdiction of Lane County appears to have been enormous, occupying nearly all of the southern half of the state, and running from the Pacific Ocean to the summit of the Rocky Mountains. Even though the current area remains large by national standards (4,594 sq. mi.), it is obviously the consequence of drastic reduction from its original approximately 140,000 sq. mi. (the size of Montana, half the size of Texas).

This reduction came about as new counties were created, taking parts of Lane's jurisdiction (and, of course, creation of the present-day State from the previous Territory). These changes are summarized in Fig. 2- 6.

It is not exactly clear when the eastern boundary of Lane was defined at its present location, the summit of the Cascade Range. An act dated December 22, 1853 defines a new southern boundary for the county as ...commencing on the Pacific coast, at the mouth of the Siuselaw on the south bank, thence following up the south bank of said stream, to a point fifteen miles west of the main traveled road, known by the name of the Applegate road, thence eastward, along the summit of said mountains to the summit of the Cascade range. (emphasis added)This would imply the existing eastern boundary. In any case, the creation of Wasco County (all of Oregon east of the Cascades) on January 11, 1854 certainly established the final eastern boundary for Lane. A series of maps which I found later[5] showed Oregon counties in 1845, 1847, 1851, 1862, 1893 and 1942. These confirmed that the state experienced further county division over a lengthy period. With the aid of these and a later set[6] I produced the maps shown in Fig. 2-7. These are shown for every year in which a change in the number of counties occurred, from the time of creation of Lane County to the creation of the last one, Deschutes, December 15, 1916. [note added 17 Jan 98: you can see an animated version of these maps].

What had not occurred to me before undertaking this study of Lane County was that the division of the state was a relatively long-term process. I had envisioned a set of "founding fathers", sitting down in a state capital and drawing a set of boundaries all at once, in accordance with the size-distance relation. This was clearly not the case in Oregon, and I wondered if it would prove to be the same in other states. Subdivision as a Continuing Process If other states were similarly divided, explaining county size became simply a matter of explaining the termination of the division process. The answer to my original question becomes: There are larger counties in southeastern Oregon because the division process didn't go as far there as it had in northwestern Oregon.

Another source[8] showed county boundaries for Illinois at present, overlaid on boundaries from 1825. In general, the farther north, the larger the county. Putnam County, along the northern border, appears to contain seventeen present-day counties Still another source[9] showed maps for all thirteen original colonies, suggesting a division process for most of them. In Pennsylvania, for example, small counties are shown for 1790 only in the extreme southeast corner of the state. To the north and west counties become progressively larger. Northumberland, currently 454 square miles, covered nearly a fourth of the state, eighteen present-day counties. A similar pattern is quite apparent for the New York counties. For California, Illinois and the larger Atlantic states, then, there does indeed appear to have been a division process similar to Oregon's. In all these cases, the division process also reflects the size-distance relation observed earlier for Oregon. That is, size increases with distance from the capital. Absence of a size-distance relation reflects completion of the division process throughout the jurisdiction of the state. Tracking down historical maps of state county boundaries in this way is not easy. Even if they are available, most state history journals are not indexed. For this reason I wrote the Geography Division of the Census Bureau to ask if they had any historical maps of county boundaries (I thought they should since they would have needed them to compute the "center of population" reported in historical censuses). The Chief of the Division wrote back informing me that the earliest maps they had were for 1930, essentially the same as the current map. What worksheets had been used for computing the center-of-population had all been thrown away over the years. It occurred to me that if a division process underlay the development of counties throughout the nation, the fact should be reflected in a growth of the number of counties in most states over time. The census volumes, from 1790 on, reported the number of people in each county, so I could check out this idea by simply counting the number of counties reporting in each state for each census year. The result of that count is shown in Table 2-1. States are listed in the table according to admission to the Union. The count for the first census year after admission is shown in red. It is obvious that, as in Oregon, many states began developing counties before statehood. West Virginia's early counties were part of Virginia until secession. Though not as conclusive as actual boundary maps would have been[10], Table 2-1 was at least consistent with a process of historical division. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TABLE 2-1. NUMBER OF COUNTIES, BY STATE AND CENSUS YEAR | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

While Table 2-1 helps explain variation in county size, it also

raises two more questions:

First, Why did counties divide as they did, when they did? (This is really just another way of phrasing the original question about why some counties are small and some are large.)

A note on Alaska and Hawaii: In this and in subsequent studies I leave out Alaska and Hawaii. Neither has counties. The island divisions of Hawaii are products of nature rather than human action; and the election districts into which Alaska has been divided have never been units of government. note added 6 Apr 1997 (the dissertation text was written in 1970): I am informed by Adrian Ettinger that two more counties have come into existence since Los Alamos, NM. In 1981, Cibola in NM, from Valencia, and in 1983, La Paz in Arizona, from Yuma. note added 4 Sep 2004: Jim Jewett sent me the following email regarding the counties of Michigan. Originally, there was Mackinaw (the first settled place), then Detroit, which quickly split into three counties, as Mackinaw came to represent "everything else". The next two counties were in what is now Wisconsin, but counties were splintered off Mackinaw as they were settled. This fit your rules pretty well, but ...It was, in fact, a very common pattern for "unorganized counties" to be officially under the jurisdiction of distant, operating county seats.

NOTES: [1] Frederick J. Holman, "Oregon Counties: their Creation and the Origin of their Names." The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, 11:1-18, 1910. [2] Franklin K. Van Zandt, Boundaries of the United States and the Several States, 242, (Geological Survey Bulletin 1212). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office). 1966. [3] The historical material here is taken from a variety of standard references (almanacs, encyclopedias, etc.). [4] The statutes are cited in Frederick J. Holman, Op. Cit.. Additional information (subsequent name changes, the dates of other counties) are from Joseph Nathan Kane, The American Counties (rev ed). New York: Scarecrow Press. 1962. [5] Genealogical Forum (compiler), Genealogical Material in the Donation Land Claims, Vol I. Portland: Genealogical Forum. 1957. [6] William Thorndale and William Dollarhide, Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc, 1987. [7] Robert W. Durrenberger, Patterns on the Land: Geographical, Historical and Political Maps of California, 59 Northridge, CA: Roberts Publishing Company. 1957. [8] Jess H. Thompson, Pike County History, 130, n.p. 1967. [9] W. S. Rossiter, A Century of Population Growth: From the First to the Twelfth Census of the United States, 1790- 1900. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909. [10] as already noted, such a set of maps now exists and does show county division in nearly all states through time: William Thorndale and William Dollarhide Op. Cit. |

I found a set of three maps

I found a set of three maps